Prior to the diet, the outlook for the new evangelical protestors was far from hopeful.

By Order of the Emperor

To develop a united front against the Turks, Emperor Charles V decreed that an imperial diet would convene at Augsburg to deal with the “evangelical problem,” among other things. The emperor announced that the diet would convene on April 8, 1530.

Prior to the diet, the outlook for the new evangelical protestors was far from hopeful. The emperor had completed his conquest of Italy and was now positioned to deal with Luther and his ilk. He needed those protecting these protestors (Protestants) to get in line and help him fight off the Turks. The only obstacle left in front of the emperor was the unresolved issue of Germany. The religious upheaval had its run, and it was time to act. Making matters even worse, the evangelical princes appeared to be hopelessly divided.

The Torgau Articles

Elector John of Torgau instructed Luther and some of his colleagues, including Melanchthon, to prepare a document treating especially “those articles because which it is said division, both in faith and in outward church customs and ceremonies, continues.” The group of men worked on the statement and presented to the elector in Torgau. This document came to be known as the Torgau Articles. The document sent to Torgau treated the following articles of faith: Human Doctrines and Ordinances, Marriage of Priests, Both Kinds in the Mass, Confession, the Power of Bishops, Ordination, Monastic Vows, Invocation of Saints, German Singing, Faith and Works, the Office of the Keys (Papacy), the Ban, Marriage, and the Private Mass.

Articles from Luther’s Pen

The Marburg Articles were authored by Luther and were the initial Lutheran statement of faith. Luther drew up these fifteen articles in 1529, six months prior to the Diet of Augsburg. It is somewhat commonly held that it was on these Marburg Articles that Melanchthon based the teachings contained in the Augsburg Confession. While it may be true that Melanchthon used the Marburg Articles as a foundational document for the Augsburg Confession, what he developed at Augsburg is a far more complete work and obviously bears the mark of his unique style and scholarly approach.

While at a stopover at Coburg while traveling to Augsburg, Melanchthon was commissioned to author what would be considered a vindication of why the Elector of Saxony had stewarded religion in his lands. Luther, who was still considered a heretic and outlaw, could not attend the diet, though he desperately wanted to go. Luther’s left the diet to Melanchthon who became Luther’s chief representative there.

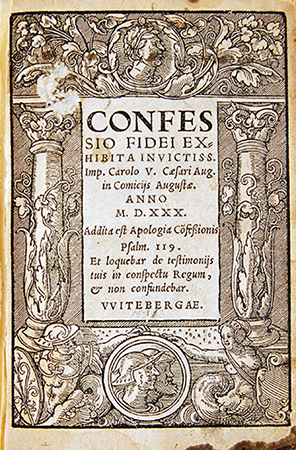

The Augsburg Confession

From Melanchthon’s Pen

Melanchthon wrote the Augsburg Confession, though he communicated with Luther daily by letter, making sure that everything was to his liking. The Catholics had relied on Johan Eck, a famous theologian, to make their argument. He did so in something called the 404 Theses. The Augsburg Confession was in some ways intended to be a refutation of Johann Eck’s 404 theses. In them, Eck found it necessary to quote out of context from Luther, Melanchthon, and other reformers such as Carlstadt and Zwingli, and he labeled them all to be heretics. What was used as the defense against Eck was Melanchthon’s Protestant confession of evangelical faith, the Augustana(Augsburg Confession).

Melanchthon had assisted in the composition of both the Schwabach and Marburg Articles. He used these prior documents and reworked the ideas therein to fit the changed situation. The time-constrained authoring of the Augustana caused Melanchthon great angst. Melanchthon was never satisfied with his own literary output, and the Augsburg Confession is no exception.

Melanchthon believed that he was compiling the true evangelical doctrine. Luther had at least in large part developed this new evangelical doctrine. Melanchthon valued Luther’s opinion highly and sent the first draft to Luther for examination. Luther returned it to him with utterances of praise. This confession was not to be the theology of Luther or Melanchthon but of the confessing evangelicals. This theology did not belong to Luther, nor did it belong Melanchthon; it belonged to Christ.

The Presentation

On June 15, 1530, the confession was read. As was Melanchthon’s habit, the Augsburg Confession was improved, polished, perfected, and partly “recast” right up until the moment it was read. Even after Luther read the document, many changes were made. It would not be until June 23 that those in attendance signed the Augsburg Confession. On June 24, Cardinal Campeggio lobbied for complete suppression of the Protestant sects. On June 25, Christian Bayer read the Augustana to the emperor and a portion of the assembly a second time. What Melanchthon had prepared at Augsburg was to become the first and formative creed of the new Lutheran Church. Dr. Bayer was to have read the document so loudly that even those standing outside the hall heard him clearly, though the emperor was said to have slept through the momentous occasion.

Signatories and Heroes

In June of 1530, the princes and electors of the free Protestant States of Saxony signed the Augustana. The Lutheran historian F. Bente says that the signers were “Christian heroes, who were not afraid to place their names under the Confession, although they knew it might cost them goods, and blood, life and limb.” Among these heroes was Elector John. Bente also notes that “when Melanchthon called the elector’s attention to the possible consequences of signing the Augsburg Confession, the latter answered that he would do what was right, without concerning himself about his electoral dignity; he would confess his Lord, whose cross he prized higher than all the power of the world.” The signing of the Augsburg Confession on June 30, 1530, is considered by many to be the birthday of the Lutheran Church

.jpg?width=80&height=80&name=staff_Headshots-(2%20of%2013).jpg)